Month: januar 2020

DARK ENTRIES INTERVIEW

DARK ENTRIES INTERVIEW

Interview med Martin Hall omkring den amerikanske Pesteg Dred-udgivelse, oktober 2010, ved Josh Cheon

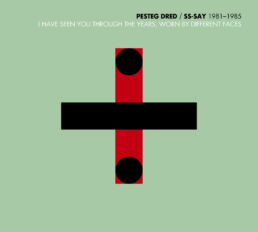

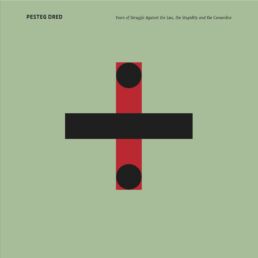

Pesteg Dred-albummet Years of Struggle Against The Lies, The Stupidity and The Cowardice blev oprindeligt indspillet I 1981, men udkom først i 1985 som et kassettebånd I forbindelse med udgivelsen af det første nummer af det danske kunsttidskrift Atlas. I 2010 udgav det amerikanske coldwave-label Dark Entries værket som vinyl-lp, en genudgivelse der modtog megen ros fra internationale tidsskrifter som bl.a. det engelske The Wire.

Det efterfølgende interview er lavet I forbindelse med denne genudgivelse.

Can you tell us a little bit about growing up in Denmark and your earliest musical memories?

– I moved around a lot. Changed school five times before 4th grade, lived in Spain with my family for a year. Aged 10 I finally settled at Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, with my mother after her divorce. By then I’d fallen completely in love with the whole glam rock thing. My first Bowie record was a cassette version of Hunky Dory. When Diamond Dogs hit the stores, I bought it during the first week of its release. Then came Sex Pistols and my life was changed forever. However, I remember listening quite a lot to Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps at this time as well, thinking that this was the music of a genius. Soon after that it was all Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach, Pere Ubu, Half Japanese and an abundance of new English music. I’m a devoted Anglophile, God bless!

How did you form the band and choose the name, Pesteg Dred?

– Well, at the time I was writing these twisted tales, long stories with a certain surreal touch. I was very inspired by writings such as Comte de Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror and Boris Vian’s books. I was in my mid-teens, my formative years. Everything needed to be reinvented, redefined, so I’d started writing. My first (unreleased) novel was called Wound landscapes and the second something even more ghastly. Pesteg Dred was, as far as I remember, a character in one of these books. Or a place. Or some entity. I actually can’t remember. The Danish word “pest” means “plague” and “eg” means “oak” which should give you a fair sense of the imagery associated with the name. The band as such was a project, a possibility myself and co-founder Per Hendrichsen had spoken about for a while. We’d been working together as an electronic unit in two different bands called Dialogue and Uté-Va. The idea with Pesteg Dred was to make music that was less electronic – the key concept being that I was going to play all the acoustic instruments and that he was going to handle the electric stuff. It didn’t really work out that way, but that was the basic concept.

How did you come up with the album title ‘Years of Struggle Against The Lies, The Stupidity and The Cowardice’?

– It was a rejected original title for a completely paranoid and misanthropic autobiography I once came across. I liked the ring of this title – the sense of utter claustrophobia and paranoia. I remember thinking that the British group New Order must had heard about the Pesteg Dred album when they released their Power, Corruption and Lies a few years later. Just joking. But both titles signify a certain zeitgeist, the “malade” of the era so to speak. The beginning of the 80’s was characterized by a radical seriousness, a Sturm und Drang attitude towards all and everything. Peel off the theatrical manners in a title like Years Of Struggle Against The Lies, The Stupidity And The Cowardice and you’re left with a guerrilla-flavoured state of paranoid defiance. Yes, the title is completely over the top, but at the same time we meant every syllable of it. The early 80’s were a very black-and-white period.

Do you remember the set-up and equipment for recording the songs from this LP?

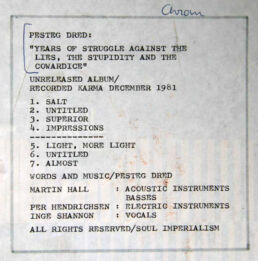

– It was a sonic raid. My band at the time was Ballet Mécanique, we had just released our debut album, The Icecold Waters of the Egocentric Calculation, but as I’ve already said, I’d been working with Per Hendrichsen in various electronic constellations. Whereas Ballet Mécanique featured instruments such as violin and cellos, Per was entirely into electronic gear. I always wondered how he got all the stuff, the Roland synhesizers and the echo boxes, ‘cause no one had ever any money at that time, least of all him. Anyway, suddenly one day Per had booked this little studio called Karma Studio for a weekend, so off we all went. I was quite surprised, since I had no idea of how he intended to finance the project. I prepared a lot of musical sketches and lyrics for the session, but once we got there it was pretty much all “shooting from the hip” – from the time of our arrival on a Friday afternoon to the final mix Sunday night. There was so little time, so most of the material on the record is first-takes. I’ve had some classical training as a guitarist, but the great thing about Per was that he actually couldn’t play an instrument – at all! What he did instead was to plug a guitar into all these wonderful electronic devices and modular systems, so whatever he played via this equipment didn’t really matter, ‘cause in the end everything was turned into this incredibly weird sounding noise. He was really good at that. However, the week after we’d been in the studio, he was due to pay the bill for the recording sessions, which he obviously couldn’t, so then the master tapes were confiscated. It was all very depressing. It took a lot of negotiation on my behalf to gain control of the material.

In 1981 you recorded two solo tapes, Ballet Mécanique’s debut album, this Pesteg Dred album, and you were only 18 years old. How did you do it?

– It’s like being in love: You don’t sit around waiting for a cue, you react to the circumstances! I loved music and I hated the claustrophobic feeling of living in Copenhagen, so spending time in various artistic environments was my way out of the misery. Already by then people were killing themselves – I mean, in the years to come my acquaintances would be reduced by something like 50% – but at the same time there was this incredible sense of possibility in everything. The punk legacy was a DIY-culture and that was how everything got achieved – you just went out and did things. It was an attitude towards life: You don’t stand a chance, so make use of it. I remember hearing this phrase and thinking, yes, that’s right, head on! Having your back against the wall both financially and existentially strengthens your determination, at least that’s how I reacted. “Perfect paranoia is perfect awareness” etc. Society as such seemed quite hostile to me at the given time, and yes, amphetamine made a lot of people paranoid, but at least it made them react. I was always straight when I was playing or recording music, the process of making it was more than enough in itself, but still it was “deconstruction time” all over the line: You had to break structures down to attain something new. Taking risks was part of the journey. The most important energy wasn’t dependent on stimulants, it came from the artistic processes. Art is a perpetual motion device, always has been, always will be.

What were the inspirations for your lyrics at this period? Why did you choose to sing in English rather than Danish?

– As I’ve already stated, I’m an Anglophile. There were about 200 people involved in the scene at the time, at max, so obviously the inspiration was coming from everywhere else but Denmark. I loved English ensembles like Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire and A Certain Ratio and the whole Disques du Crépuscule thing going on in the Benelux countries. This was the kind of environment you wanted to connect to and communicate with, not some patronizing old guy ruling a local newspaper in Copenhagen. We wanted to communicate with like-minded individuals. I remember receiving a written letter from Larry Cassidy, the singer and bass-player in Section 25, in response to a line of questions I’d sent him after hearing the group’s first single “Girls Don’t Count” in 1980. He’d even sent me a cassette tape with the demos for their upcoming album Always Now. I was so thrilled. The world felt so close at hand!

The Pesteg Dred LP was recorded in 1981, but remained unreleased until 1985 when it was issued as a bonus cassette along with the magazine Atlas. Why the long stretch of time and limited tape format?

– As I said, we had some problems with getting the master tape released from the studio due to the missing payments. Inge (Shannon, the singer in Pesteg Dred) suffered a nervous breakdown shortly after recording the album and we were all going through some difficult times. In October 1983 my next band, SS-Say, made its debut at the legendary William S. Burroughs visit in Copenhagen. We used another singer at the time, Inge being quite retreated in that period, but at some point the people arranging the Burroughs-visit began talking about including the Pesteg Dred album with a new art magazine they were planning to make. It seemed like a perfectly good idea. Before they came around to do so, Inge had joined SS-Say and things were on the move again. Everything came together in 1985: SS-Say released ‘Fusion’ and Atlas, the art magazine, made the Pesteg Dred material available as a cassette. One of the people behind Atlas was Danish painter and musician Christian Skeel, so obviously it had be his artwork on the cover of the Pesteg Dred re-release. There’s a certain sense of symmetry in it all – both in the design processes as in the inter-development of the two bands.

I first heard the song “Care” by SS-Say in a goth club in New York City and to me the vocals captured such intense emotion. I found the song trapped in my head for weeks. The vocalist, Inge Shannon, she displays her vocal range quite proficiently. How did you meet her?

– Inge was one of the first punks in Denmark. It was even her graffiti shown on the back cover of the first real Danish punk-lp, the Minutes To Go album with The Sods. She sprayed the band’s name and logo on a train station somewhere in the suburbs to Copenhagen and the group used this motive as the back cover illustration on the lp-release. Per Hendrichsen and Inge had known each other for some time by then. I met her when I began going to punk concerts in 1978. She’s a very gentle individual, a very pleasant person to be with. To me it was quite obvious that she should be a singer in a band – she just had that kind of thing to her. I love Inge’s voice, but she never really considered herself a singer. She didn’t particularly like the sound of her own voice, she actually found it quite embarrassing. She had recorded a few tracks with Per Hendrichsen for a tape he’d once made, that was it as far as her singing was concerned, so the Pesteg Dred recordings represented a big step to her. Shortly after the sessions she had this breakdown I mentioned and was pretty much out of circulation for a few years, but when she joined SS-Say in 1984, she had become such a great singer.

For many people this will be their first time hearing Pesteg Dred. Do you have any listening instructions for them?

– No. Music shouldn’t be defined as such, it either has an impact on you or it doesn’t.

Did Pesteg Dred ever play live or tour? Can you describe your most memorable/favourite live gig with this band?

– We never played live with Inge. Later on me and Per made a version of the band with two bassists – one of the being the Danish painter Peter Bonde, a later professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts actually ¬– but it was all instrumental, basically me banging away on the drums and Per making all this god-awful noise with his guitar amplifiers and modulations.

How do you feel about the renewed interest in your earlier music?

– It seems like a logical consequence in many ways. Not that I consider it particularly divine or anything, it just has its own sense of a natural vigour. And then it seems to be a kind of unwritten law, that if something is enough out of sync with everything else at the time of its conception, it’s probably going to stand the test of time.

What music are you currently listening to these days?

– Quiet stuff. I like Goldmund’s records – his music seems to capture the essence of my current needs. Recently deceased French composer Hector Zazou’s ‘In the House of Mirrors’ has been another one of my favourite records lately.

I know you remain active in the worlds of art, music and writing. What are your current musical projects and plans for the future?

– I’ve just released a new novel, a book called Kinoplex, and the whole prospect of writing is getting more and more serious to me. I’ve also written a line of new music with Christian Skeel for the audiobook version and I’m going to perform Kinoplex as a stage play as well – with a narrator and a small ensemble – during October and November this year. So there’s a lot of activities going on as far as this material is concerned. Furthermore I’ve been playing with internationally renowned classical accordionist Bjarke Mogensen and string-bassist Ida Bach Jensen in relation to a series of spoken word-concerts recently. I basically find myself involved in a lot of stimulating projects at the moment. Last week my St. Paul’s live-performance was released on DVD and a few hours ago I delivered a contribution to the next Second Language soundtrack. I’m also planning to record a new album during 2011, but as with all things, you can only plan so much ahead – the rest seems to happen to you all by itself.

PARADE

PARADE

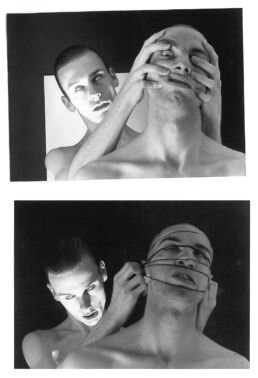

Parade var en multimedieforestilling med The Body Art Ensemble of Copenhagen, videreførelsen af Martin Halls eksperimenterende 1982-teatertrup The Art Ensemble of Copenhagen. Halls samarbejdspartner i The Body Art Ensemble of Copenhagen var Henrik Möll.

Parade var skrevet og iscenesat af Hall og blev opført hen over to aftener i Saltlageret i december 1984. Det var bl.a. under denne forestilling, at Hall og Möll skar sig selv til blods på scenen, imens der blev projiceret film af de to hovedpersoner i færd med at udføre oralsex på hinanden. Recitationer blev for de to frontfigurers vedkommende udelukkende foretaget via i forvejen indspillede passager, der blev afviklet over håndholdte walkman-båndoptagere – al anden fortællevirksomhed blev afspillet som enten playback-speak eller foretaget live af de andre skuespillere via megafoner.

Andre medvirkende i forestillingen var Jan Munkvad, Asger Gottlieb, Janine Neble og Jens Kruse. Sidst, men ikke mindst medvirkede Martin Halls far, Eigil Hall, også – han spillede flere roller, dels invalideret sprechstallmeister, dels – i forestillingens sidste scene – en afklædt Jesus Kristus. Eigil Hall havde overtaget rollen fra Elsebeth Hall, Martin Halls mor, der havde begået selvmord nogle måneder inden forestillingen. Hun skulle bl.a. have spillet rollen som kvindelig Kristus-figur.

Hvor The Art Ensemble of Copenhagen’s 1982-forestilling Giv Folket Brød, Vi Spiser Kage var præget af en stor portion humor, var Parade kendetegnet af en total mangel på samme element. Manuskriptet til Parade er desværre gået tabt, men du kan læse noterne til 1982-forestillingen her.

Fotos: Kurt Rodahl

BREMEN TEATER

BREMEN TEATER

Da Martin Hall lørdag den 20. oktober 2018 spillede på Bremen Teater, skete det efter fem års live-pause. Med sig på scenen havde han et 6-m/k-band bestående af både elektriske og klassiske musikere, og materialet strakte sig fra helt nye numre til adskillige overraskelser fra bagkataloget.

Især nummeret ”Free-Force Structure” kom bag på mange, eftersom Hall ikke havde spillet sangen live siden 1985. Blandt aftenens andre sange fandt man også “Muted Cries”, “Poem”, “Dead Horses on a Beach”, “Another Heart Laid Bare” og “Images in Water”.

En anden af aftenens store overraskelser var, da den tidligere SS-Say-sangerinde Inge Shannon trådte ind på scenen for at synge gruppens gamle coldwave-klassiker ”Care” sammen med Hall.

Musikerne til koncerterne var:

Christine Raft (flygel og violin)

Johnny Stage (guitar og sitar)

Una Skott (guitar og keyboards)

Andreas Bennetzen (kontrabas med bue)

Sisse Selina Larsen (trommer og percussion)

Koncerten modtog en række fremragende anmeldelser, hvor nok især Simon Heggums GAFFA-anmeldelse satte ord på den oplevelse, mange i salen havde haft. I artiklen Den overmedicinerede søn vendte hjem tildelte han ikke alene aftenen 6 ud af 6 stjerner, men indledte eksempelvis med at skrive følgende:

”At tale om, at et land kan være for lille til en kunstner, kan lyde som lidt af en overdrivelse. Men i tilfældet Martin Hall er det ikke desto mindre rigtigt.”

I sin opsummering af koncerten konkluderer han:

”En betagende koncertoplevelse – en af de stærkeste danske koncerter, jeg har været til i de senere år.”

Du kan læse hele anmeldelsen her:

Da GAFFA i et interview kort inden havde spurgt Hall, hvad man kunne forvente af efterårets koncerter, lød hans svar som følger:

”Der kommer et par overraskelser, der givetvis vil glæde dem, der har fulgt mig siden de tidlige dage. Men publikum må også være indstillet på, at det handler om 2018, dvs. om hvilke numre, der føles aktuelle at spille nu og her. Det er ikke mit bord at servicere nostalgikere. En Martin Hall-koncert skal ikke tilbyde for megen pædagogisk vaseline, det skal være en hyldest til voldsom, klassisk skønhed, til utilpassede sjæles febervildelser og til Weimar-republikkens outrerede cabaretscene. Der spilles ikke op til fest i denne her klub, det handler om at kommunikere århundredetunge følelser videre, om at trænge igennem tidens absurde facadeidentitetsdyrkelse og prangende ligegyldighed. Leben und Kunst, verdammt!”

Læs hele interviewet her.

Alle livefotos i højre kolonne: Maiken Kildegaard

De følgende billeder er taget ved nogle af de andre koncerter, Hall spillede i løbet af oktober 2018. Fotograferne her er Bjarne Christensen og David Faurskov Jensen.